There are no winners or losers, said Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the “historic” Paris Climate Accord adopted late Saturday night, but with impending closer global scrutiny, India is set to come under huge pressure to increase its targets for cutting the levels of greenhouse gas emission.

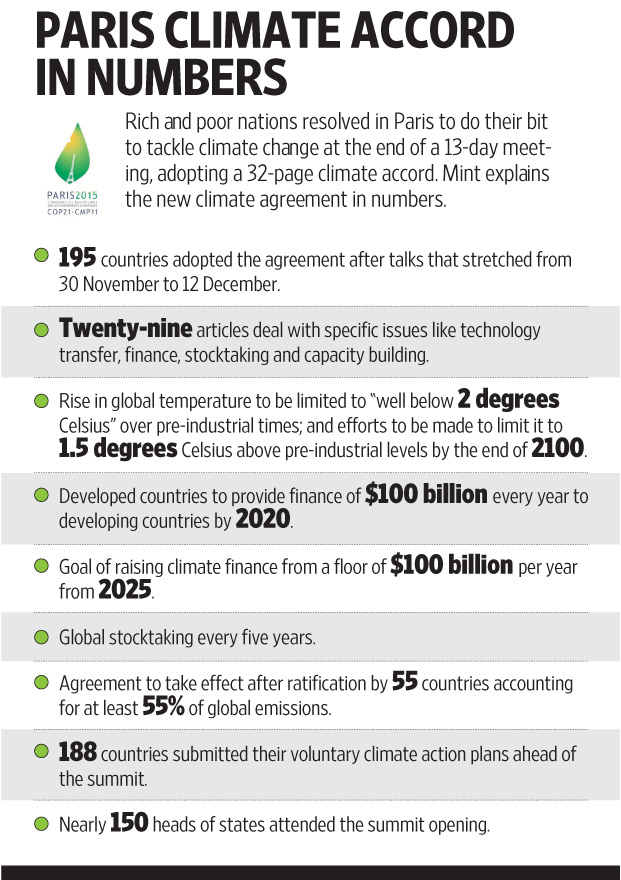

As the brackets came off disputed sections of the final draft of the agreement at the close of two weeks of negotiation in Paris, some experts took a measured view of the document that was endorsed by 195 countries.

Experts called the deal unambitious and said it would only increase the vigil on emerging industrialized economies, such as India, which have come under mounting pressure to do more to combat climate change.

Modi, who attended the inauguration of the summit, said after the agreement: “Climate justice has won, and we are all working towards a greener future. Climate change remains a challenge but the Paris Agreement demonstrates how every nation rose to the challenge, working towards a solution.”

The 32-page accord, reflecting global consensus to move away from burning fossil fuels, was agreed on Saturday evening after 13 days of intense negotiations and three draft texts. Differences prompted organizers to extend the summit by a day, but effective diplomacy by hosts France helped the world avoid possibility of a last-minute collapse of talks.

The negotiations were aimed at agreeing on a new roadmap for cutting greenhouse gas emissions so that the average global temperature rise can be kept below 2 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level.

But the deal, which will be implemented from 2020, has compromise written all over it— the product of a give-and-take between the rich and developing countries over several prickly issues, including helping developing nations financially in their move toward a green future, and whether rich nations, with their historical responsibility, have to do more than poor countries in combating climate change.

And although the meeting was of the Conference of Parties 21 (COP21)—within United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC)—the final agreement has sidestepped many hard decisions mandated under the original UN climate convention of 1992.

These include marking out a clear differentiation between developed and developing countries on actions such as emission reduction.

The biggest change incorporated in the Paris pact is a call for developing countries—and not just the developed countries—to take publicly announced emission reduction actions, unlike in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol where only rich nations were required to do so.

Environment minister Prakash Javadekar, leading India’s delegation, said: “The Paris Agreement does not put us on the path to prevent temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius, and the actions of developed countries are far below their historical responsibilities and fair share. While give-and-take is normal in negotiations, we are of the opinion that the agreement could have been more ambitious.

“We have in the spirit of compromise agreed on a number of phrases in the agreement. I hope that Paris will mark the new beginning, where commitments made will be fulfilled.”

Countries also decided to take stock of the progress—of actual reductions in carbon emissions and provision of finance—in 2023, to begin with. The five-yearly audit makes a collective assessment on whether the targets agreed in Paris are enough to keep the temperature under check. Any increases in targets would be voluntary and “nationally determined”.

The agreement sets the deadline for net zero emission of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century—that is, between 2050 and 2100.

This offers a measure of comfort for the developing countries, such as India, as it helps give a clear signal about the direction of the economy and a guide to investors on the sectors they should invest in.

Renewable energy emerges as a major potential gainer as India’s target is to have nearly 40% of its power from renewable sources by 2030, even though more than 50% would come from fossil fuel sources like coal.

India has also set itself the ambitious target of increasing coal production from 565.77 million tonnes in 2013-14 to 1.5 billion tonnes by 2020 to reduce dependence on imports. India is focusing on more efficient thermal power plants to curb pollution.

“A close scrutiny is needed to understand the exact changes India will have to make in its policies. But in energy, transportation and agriculture policies, changes will be required,” said Prodipto Ghosh, a former secretary of the environment ministry and distinguished fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), an environmental think tank. “We will now be under strict surveillance as to whether we are able to meet our targets of reducing carbon emissions. The situation is such that availability of concessional finance is virtually ruled out.”

The Paris agreement commits developed countries to provide finance of $100 billion a year by 2020, but this pledge is ambiguous and lacks a clear roadmap. It also provides for setting a new collective quantified goal from a floor of $100 billion per year from the year 2025.

This was one of the thorny issues between the rich and developing nations, and experts said the ambiguity now leaves the door open for claiming multilateral loans and bilateral developmental assistance as part of such climate finance.

This weakens the stand of countries like India who wanted a clear roadmap for finance in order to move to cleaner technologies.

India, meanwhile, claimed success in ensuring words like “equity and common but differentiated responsibilities” mentioned in many places. However, these are only suggestive references, without any real commitment.

On the issue of differentiation, which sets apart developing and developed countries, it was a “win some, lose some” agreement for the developing world.

There was tremendous pressure from countries such as the US who wanted the concept of differentiation to be scrapped but in the end, developing countries were able to keep it intact across several sections.

However, in the case of emission reduction targets, the developed world was able to get more flexibility for their obligations than they had under the Kyoto accord.

Despite India’s claims of pushing the concept of climate justice, the country will be under constant pressure to take on more responsibility for mitigating climate change by 2020 and beyond, said the Centre for Science and Environment, a think tank.

French President Francois Hollande called the deal the first universal agreement in the history of climate negotiations.

Experts, however, had a different take, some calling it weak and toothless.

Benny Peiser, director of the Global Warming Policy Forum, a London-based think tank, called it a “non-binding and toothless UN climate agreement”. “The Paris deal is based on a voluntary basis, which allows nations to set their own voluntary CO2 targets and policies without any legally binding caps or international oversight,” said Peiser.

Sunita Narain, director general of CSE, said: “On the whole, the Paris agreement continues to be weak and unambitious, as it does not include any meaningful targets for developed countries to reduce their emissions.”