SHANGHAI—China is trying to alleviate a pair of knotty problems—population pressure on its biggest cities and a glut of new homes elsewhere—by getting smaller urban areas to offer housing discounts to attract migrants from the countryside.

Encouraged by Beijing, some local governments are rolling out a range of housing subsidies, tax waivers and lower mortgage rates to attract new residents. In Fuyang, an urban district near the well-off eastern provincial capital of Hangzhou, the government is providing a one-time housing subsidy of as much as 800,000 yuan ($123,874) for new residents with certain qualifications who buy homes in the area. The central city of Luoyang is subsidizing deed tax payments and mortgage costs for rural migrants buying homes in the city.

The push by Beijing is intended to address a problem that has cropped up in recent years as people leave the countryside for the cities for work: Most want to go to the largest, most prosperous cities, putting a strain on infrastructure and services in those places. Meanwhile, large parts of the rest of the country are overbuilt.

A result of this divergence is that, while property prices are recovering in Beijing, Shanghai and some other major cities, years of overbuilding plague most other urban areas and amount to a sizable drag on the economy.

“It is becoming clear to Chinese officials that the property sector still retains an important role in stabilizing the economy,” said Chen Sheng, who heads the government-backed China Real Estate Data Academy. “The idea is to stabilize, not to overly stimulate the economy.”

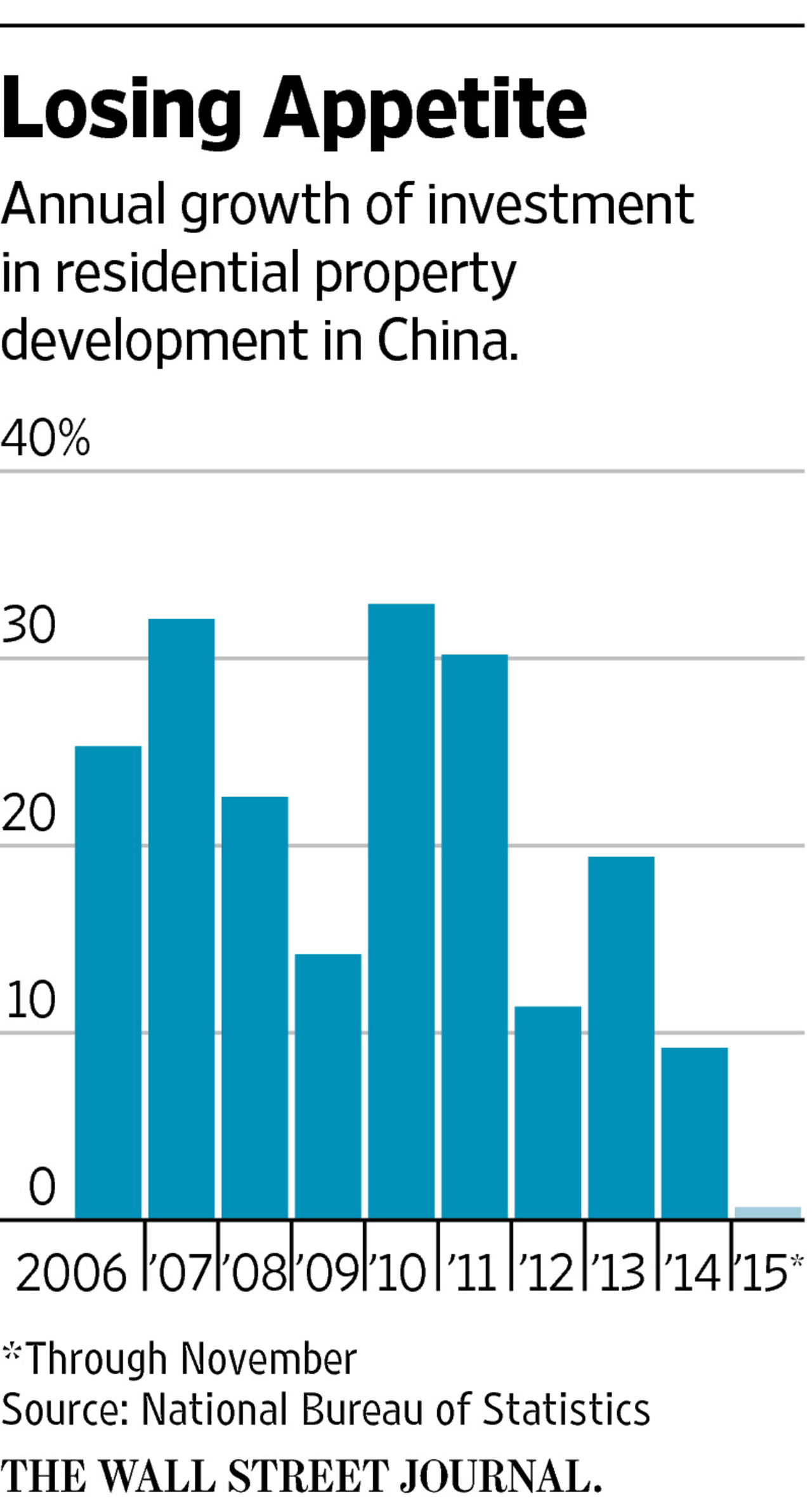

While housing sales have rebounded this year, investment in real-estate development has slowed to 1.3% in the first 11 months this year from the same period a year earlier, while construction starts declined 14.7% over the same period.

Last month, President Xi Jinping told a meeting of economic and financial officials that China must resolve the housing inventory situation and ensure the health of the property sector.

The efforts to divert rural migrants to smaller cities comes amid a renewed effort by Beijing to improve the treatment given to rural migrants.

The State Council, the government’s executive body, over the weekend issued new guidelines for local governments, telling them to offer a more comprehensive package of benefits, from housing loans to social services, to incoming residents, who may not have the proper household registration documents, known as a hukou.

The hukou system was imposed decades ago to keep rural Chinese out of cities, when China was much poorer. It has evolved into a benefits management system, defining access to health care, employment, education and other social benefits. Typically those benefits are better for those with an urban hukou, and the current system has been widely criticized as unfair by often denying holders of a rural hukou access to those services in the cities to which they move.

Smaller cities have in the past tried to draw in rural migrants by offering them urban hukou. But still migrants have preferred larger cities with more vibrant job markets. And some analysts have said that cities will have to do more than offer lower housing prices.

Liu Dan, a Hangzhou-based fashion designer in her mid-20s, says that apart from housing costs, she will have to assess job prospects, social networks and proximity to her family in the northwestern region of Xinjiang before considering settling down in a city.

“It is about being familiar with a place,” said Ms Liu, who has worked in Shanghai and Qingdao before. “I’ve been in Hangzhou for more than a year now, but I’m still not used to this place.”

Some analysts have voiced skepticism that urbanization will cure China’s housing surplus, noting that in some places, it is becoming more difficult to get rural dwellers to uproot themselves.

“There is a perception that there isn’t much benefit moving into the city,” said Song Huiyong, research director at property consultancy Shanghai Centaline Property, adding that smaller housing units and mediocre employment prospects stemming from a slowing economy deter them too.

“They also know their rural land is worth more now, and are unwilling to give up those rights.”

Many of these subsidies are temporary, lasting only a few months as questions remain on how local governments could raise money to foot the bill for these costs. Some local governments have also asked state-owned firms and financial institutions including policy banks to help with these costs.