Chinese leader says ahead of UK visit that he will focus on increasing overseas trade relationships, including starting a ‘golden era’ with Britain.

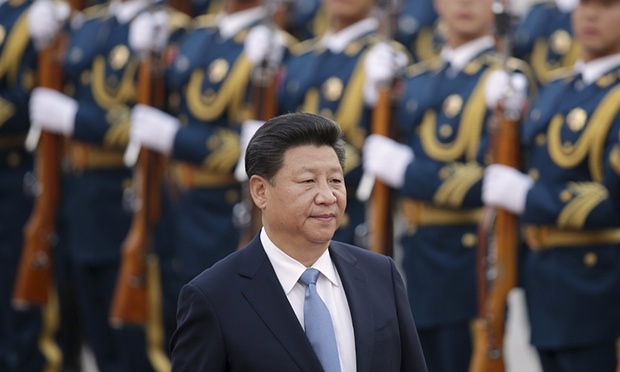

Xi Jinping has acknowledged that China’s leaders are concerned about the economy, but described the problems as “growing pains”, as he prepared to leave for his first state visit to the UK, bringing with him billions of pounds of planned investment.

In the wake of stock market jitters that rocked China and the wider region recently, and with imminent growth figures likely to confirm the slowest growth rate since 2009, the Chinese president said China was looking to external deal-making with countries such as Britain as a way of diversifying its economic base.

“We do have concerns about the Chinese economy, and we are working hard to address them,” Xi said in written answers to questions put by Reuters on Saturday. “We also worry about the sluggish world economy, which affects all countries, especially developing ones.”

The solution, he said, was to open up the Chinese economy to more foreign investment and encouraging the country’s firms to invest overseas. The four-day visit to Britain, which officially starts on Tuesday, is aimed at facilitating both. About 150 deals are expected to be sealed this week in areas such as healthcare, aircraft manufacturing and energy.

China has been basking in its role as the motor of global growth and a generator of wealth and jobs envied by the other big powers. But beneath the headlines lurk persistent questions about the sustainability of Chinese economic power: the stock market volatility that rattled the authorities this summer, a mounting regional debt bubble fuelled by years of cheap money, faltering exports, and weak consumer confidence.

“We have warned for years that China was at risk of a hard landing,” said experts at Fathom, a London economics consultancy. “Since June, when China’s stock market first started to falter, sentiment surrounding China and its prospects for growth have deteriorated markedly. Many now widely dismiss China’s official GDP statistics as little more than propaganda.”

Prof Michel Hockx, the director of the SOAS China Institute, said Xi was coming to Britain with clear economic objectives. “The Chinese economy is slowing down and it is changing its nature from an investment-driven growth economy to an economy that has to look to invest in other places,” he said. “Chinese businesses are very eager to invest in other countries, and some of the best export products that China has to offer are to do with infrastructure, high-speed trains, energy, things like that, and these are exactly the things that the UK needs.”

The trip, Xi’s first to Britain as president, has been hailed by British and Chinese officials as the start of a golden era of relations that the Treasury hopes will make China Britain’s second-biggest trade partner within 10 years.

In his interview with Reuters, Xi recognised there were misgivings about the relationship between Beijing and London. But he added: “No country can afford to pursue development with its door closed. One should open the door, warmly welcome friends and be hospitable to them.”

He also spotted a less obvious area for cooperation: football. “My greatest expectation on Chinese football is for the Chinese team to be one of the best in the world,” Xi said. “China and the UK have had good cooperation on football in recent years. In 2012, a cooperation programme was launched to promote football in schools and the UK started to train Chinese football coaches at the grassroots level,” he noted.

“Last month, the two countries signed an MoU [memorandum of understanding] to produce future stars in football. In the next five years, football training will be introduced to 20,000 Chinese schools, which means huge potential of cooperation between China and the UK in the training of players, coaches and referees.”

Howie said Beijing would revel in the pomp and circumstance of this week’s visit. “They will be looking for horses and people in funny hats and meeting the Queen. That plays fantastically well back in China and they make big use of that to show how important the Chinese leadership is,” he said.

“It also plays to the pitch that China is now being recognised on the world stage as a great power. This is especially true in Britain’s case, because it was those nasty Brits who beat them in the opium war. Now the tables have turned and it is China in the ascendancy and it is Britain who is pandering to the Chinese.”

Prof Kerry Brown, the director of King’s College London’s Lau China Institute, said Beijing would be glad to deal with an increasingly compliant Britain. “The Chinese have dealt with the British for a long time, since [George] Macartney’s mission to China in 1793. So they are practised at the brilliant complexity of British hypocrisy, and I think they are very comfortable dealing with that. This works well for them.”