Big bang economic reform is politically risky for the BJP, whose first priority is to replace the Congress as India’s default party.

In India, it is often argued that good economics is bad politics and bad economics is good politics. There is a perception that free-market reform rarely wins elections. India’s favourite reformers Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Chandrababu Naidu all bit the dust at the hustings. Equally, there is a perception that populism wins; Sonia Gandhi in 2009, Y. S. Rajasekhara Reddy in 2004, the Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu. Narendra Modi’s historic 2014 win against the populist United Progressive Alliance might have buried that ghost. But it likely hasn’t. The reality is that the relationship between economic reform and political success is more complex than simple clichés. The fact is that while on balance a greater number of people will gain from economic reform, some will lose. And in democracies, the losers can often command the louder voice, with some help from opportunist political parties.

An astute politician like Mr. Modi knows that. He also knows that while in Gujarat economic reform may have translated into good politics (as seen in the repeated elections wins), the same equation may not add up elsewhere in India. Any assessment of Mr. Modi’s record in office must recognise this tension (often perceived and sometimes real) between economics and politics and the fact that for Mr. Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party, his unique mandate isn’t just about an economic project to transform India. It is also about a political project to grow the BJP as a political party, to install Chief Ministers in States it has never held power in before, and to eventually replace Congress as the default party of governance in India.

If you ask a BJP member what the high point of Mr. Modi’s first year in office was, many would probably say the party’s twin victories in Maharashtra and Haryana in October 2014, when Devendra Fadnavis and Manohar Lal Khattar became the first-ever BJP leaders to rule those States. The BJP (or should we say Mr.Modi and Amit Shah) had succeeded in storming two new bastions within six months of the general election.

Reforms come second

Those expecting Mr. Modi to push ahead with radical economic reform in his first six months (the honeymoon period) — whether on labour laws, land acquisition or even FDI — were always going to be disappointed. Put simply, those reforms, whether necessary or not, would have given a stick that the Opposition could wield at Mr. Modi and the BJP. The political project demanded clear priority. The Modi wave could not be disturbed by the logic of economic reform. Imagine the political controversy that the amendments to the land bill would have caused in Maharashtra and Haryana, two States where a lot of land acquisition by industry actually happens. Unsurprisingly, elements of the reform process — on land, labour and FDI — picked up after those two elections and have, at the least, created some political storm.

How does the defeat in Delhi in February 2015 fit into this narrative? Was that a vote against the lack of reform and the growing disillusionment with Mr. Modi? Was it a setback to the political project? The answer to the second question is no, because while the defeat in Delhi was a blow to the BJP, the party retains a strong presence (it is the second biggest party and ahead of the Congress by miles) and is well placed to capitalise on AAP’s non-performance. The answer to the first question isn’t so obvious. It probably was a vote that signalled impatience with a lack of outcomes, rather than a vote for or against a particular set of policies.

More elections up ahead

Going forward, the BJP has a crucial political project coming up in Mr. Modi’s second year in office — the Assembly election in Bihar in September-October 2015. That is another State where the BJP hasn’t had a Chief Minister and has been in government previously only as a junior partner in a coalition. The Modi-Shah duo will want to change that. Now, Bihar’s electorate is probably not so bothered about FDI, land or labour reforms because the State has very little investment and industry in any case. But Bihar’s electorate would be greatly concerned about subsidies (particularly food and fertiliser) and government welfare programmes, including the Congress-founded MNREGA.

The logic of economic reform requires that Modi’s government take firm steps to rationalise subsidies (many of which are lost in corruption) and cut down unproductive government spending on populist schemes to divert it to productive investment in infrastructure. Again, there has been disappointment among supporters of reform on the lack of concrete action on this front. If anything, Messrs. Mr. Modi and Mr. Jaitley have committed more money to MNREGA than the Congress did. But repealing any major subsidy or abolishing a populist government programme would give the Opposition in Bihar something to beat the BJP with. Such radical reform, while good in the long term, entails a political risk in the short run. The Opposition would go on overdrive arguing that Mr. Modi has cut spending on the poor and that his policies are pro-rich. The BJP government next faces an election in 2019, but the party has to battle in different States every year. The smaller political projects must also be kept in mind.

It is perhaps peculiar to India that the country is in a continuous election cycle. After Bihar, it will be West Bengal’s turn in 2016 — another State where the BJP wants to make inroads. In 2017, it will be Uttar Pradesh where the BJP will want to reclaim power after more than a decade. In 2018, its core States of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan will go to the polls. When the larger political project isn’t simply to win re-election in 2019, but also to extend the party’s reach in other States, Mr. Modi has no honeymoon period to take what might be difficult economic decisions.

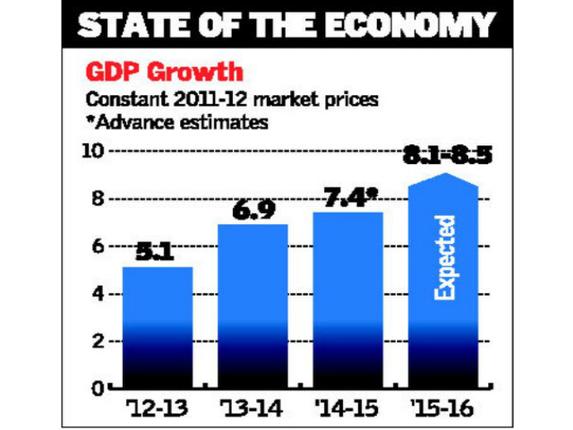

That is probably the best explanation for the chosen path of creative incrementalism on economic policy rather than big bang reform. In Mr. Modi’s view, that may be the only way to balance the logic of winning elections with the need to power growth. That is why, in the BJP’s view, the first year of Mr. Modi’s government has been quite a success.

(Dhiraj Nayyar is an economist and columnist.)

Keywords: Modi 365, economic reform, economic policy, BJP, NDA government