The South African economy was gazing into the abyss but, when President Jacob Zuma announced the removal of finance minister Nhlanhla Nene on Wednesday night last week, it was pushed over the edge.

Observers say, without restoring confidence by appointing Pravin Gordhan, the economy was going into free fall, with the rand becoming a one-way bet and the country heading for an economic apocalypse.

In the worst-case scenario, the currency would have continued to weaken, potentially past R20 to the dollar. Inflation would have rapidly escalated, forcing the Reserve Bank to hike interest rates aggressively, which would have further slowed economic growth. Resultant credit-rating downgrades and high bond yields, coupled with large capital outflows, would have made the cost of government funding unsustainable.

Under these circumstances, the country may have had to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout.

After Zuma’s appointment of Des van Rooyen as finance minister last Wednesday, the rand rapidly weakened, passing the R15 to the dollar mark. In the next two days, the stock market lost R230-billion in value and the bond market R217-billion, equal to between 10% and 15% of the economy, said Adrian Saville, the chief strategist of Citadel, in a note.

“The loss of R437-billion wiped out the equivalent of two years’ worth of economic growth from South Africa’s savings pool,” he said.

The chain of calamitous events were stalled when, on Sunday night, the decision to put Van Rooyen at the helm was reversed and it was announced that the fiscally prudent Gordhan would be finance minister.

“Van Rooyen was the fast track to the IMF. We could have been downgraded by the middle of next year, maybe with a negative outlook,” said an economist who asked not to be named.

Andrew Canter, the chief investment officer of Futuregrowth Asset Management, said Van Rooyen was an as yet “an unknown and untrusted” finance minister as far as markets were concerned. “And in the absence of Sunday nights’ reversal of policy, we would have woken up on Monday morning to continued crisis … The way the markets were reacting, this thing was going to get ugly very, very quickly. In economic terms, that means 12 to 18 months.”

Interest rates would have continued rising, and the Rand would have continued falling, said Canter. “In light of the dramatic policy uncertainty that the initial change of minister of finance brought, it was unlikely anyone could have rationally stood in the way of the selloff.”

Following Nene’s removal, the emerging markets analyst of Nomura, Peter Attard Montalto, said the rand at 16 to the dollar did not seem an outrageous target.

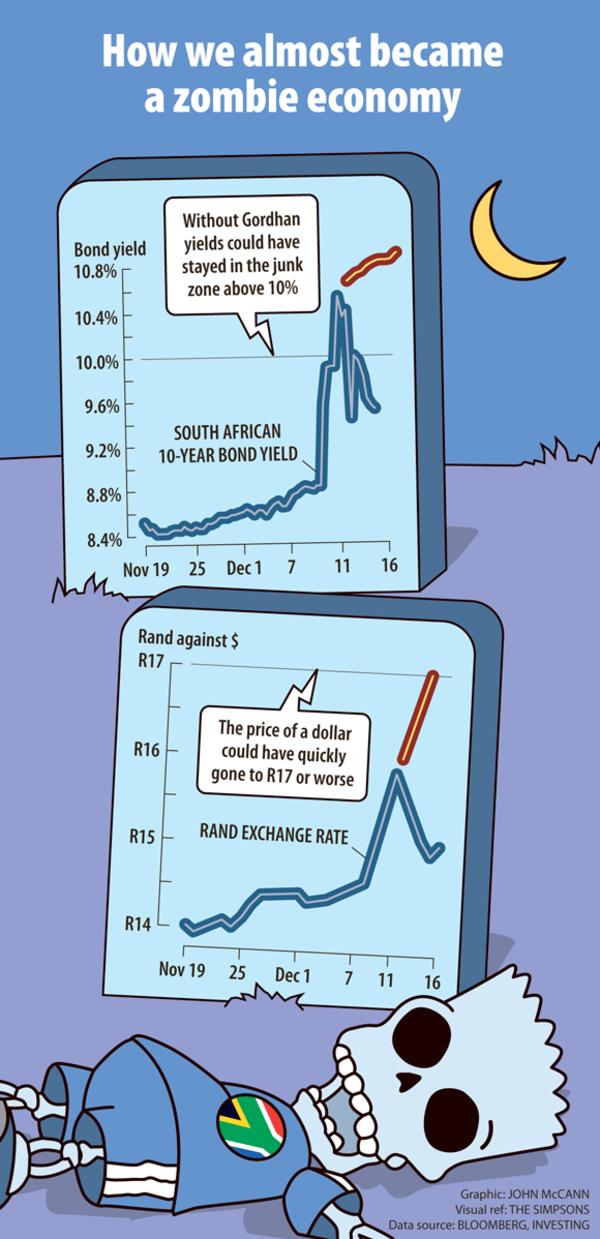

Mike Schussler, the director and chief economist of economists.co.za, said Gordhan stepping in as finance minister probably stopped the rand from reaching about 17 to the dollar by Tuesday this week.

Azar Jammine, the director and chief economist of Econometrix, said the scenario most people feared was hyperinflation in the long term. “We could have had a free fall in the rand. There is no saying how far the rand could have fallen.”

The weak currency would quickly push up inflation and force the Reserve Bank to raise interest rates to keep it under control.

“In a worst-case scenario, we would have seen the Reserve Bank likely compelled to hike rates very aggressively, and that could have precipitated a very deep recession,” said Mohammed Nalla, the head of strategic research at Nedbank Corporate and Investment Banking.

Attard Montalto, last Thursday, predicted a possible 50 or even 100 basis points hike in January, depending on movement of the rand and outflows. He even warned that political influence could extend to the Reserve Bank, which, like the treasury, “could no longer be viewed as sacrosanct”.

The prioritisation of political issues over reforms put South Africa firmly on the path to junk status, he said. Before Gordhan was brought in, Attard Montalto said he expected ratings agencies to downgrade South Africa, possibly after the February budget.

The unnamed economist said that with a downgrade to junk status, some investment would be forced to leave. “This would take the rand on a very rapid trajectory to even above 20 to the dollar.”

It would also take the government’s funding and debt servicing costs, already a concern for ratings agencies, to unsustainable levels, meaning its infrastructure programme, the core of its economic programme, would have to be curtailed.

Attard Montalto on Thursday last week predicted the bond curve could have been rerated to around 10% to 10.5%, which it had by Saturday. This would severely stress the budget, he said.

Had there been no intervention, Shussler said the government long bond would have been more than 10%, where it was on Sunday. “That is very much a junk rating yield.”

He said these higher bond yields would have increased the cost of borrowing by more than R5-billion a year “and government would have had to take that at least that from spending plans every year from now on”.

After Gordhan’s appointment, the 10-year government bond yield had dropped to 9.5% by Wednesday. Had the situation continued to regress, it might not have been a very long walk to the IMF.

“The bond yield would have to be around 15% for the IMF to come in. That’s 50% above a junk bond yield,” said Shussler. “If we get to a difference of 1?000 basis points or 1?300bps between ours and the US bond yield, that is really problematic.”

Attard Montalto told the Mail & Guardian: “The real question is whether you would have had a financial stability event.” That, he said, would have been guided by changes in policy related to nuclear procurement or decisions about the SAA Airbus swap deal.

Had there been more of a “shock outflow”, there may have been a current account event, such as a sudden stop in the balance of payments. “Failed bond auctions [where investors are not interested in buying government bonds] might have happened in the new year,” he said.

The unnamed economist said: “You get to the IMF when you start getting failed auctions domestically, so you don’t have sufficient resources to import what you need.”

Nalla said: “The hardest hit in that doomsday scenario would always be the poor.”

Gordhan’s appointment has reversed some of the damage, but certainly not all.

Jammine said: “Even now, the rand has not recovered to where it was. It means we will still have higher inflation than anticipated. Interest rates will have to rise. There will probably be a rate hike in January and March.”

Shussler said: “This thing was real and it is real … Part of this cost will remain. People were hoping we would go back to 9.5 or 10 to the dollar. That is definitely not going to happen now.”

Tshepiso Moahloli, the treasury’s chief director of liability management, said higher bond yields might mean the government will have to issue more debt to meet the borrowing requirement, which would result in higher debt service costs.

“Should domestic government bond yields in 2016-2017 be 100 basis points higher than the forecasted yields used to calculate the debt-service costs published in the 2015 MTBPS [medium-term budget policy statement], debt-service costs on domestic government bonds will increase by R1.5-billion in 2016-2017,” Moahloli said.

Canter said: “The biggest impact is that trust has been broken and this inevitably leads to higher risk premiums on South Africa’s global bonds. “Even with the reappointment of Pravin Gordhan, it’s going to take a while to get through the inflationary consequence of the Rand’s fall and then rebuild trust. That means interest rates will rise faster and stay higher for longer than would otherwise been the case.”

Nene’s exit magnifies concerns about South Africa’s Achilles heel – and that is the budget story, said Luis Costa, fixed income and FX head for Central and Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa at Citigroup.

“Normality, I don’t think we will go back there. South Africa is on the back foot,” said Costa. “Unless treasury unveils something more powerful in the next two months, this process will be quite nervous.”

Said Canter: “The greatest outcome of all of this is that democracy actually works. Still, we had to stick a knife in our foot to get there.”

Fed rate hike pales next to Cabinet reshuffle

The United States Federal Reserve has hiked interest rates after months of speculation that contributed to increased pressure on emerging market currencies, including the rand.

But the currency reacted relatively mildly after the announcement on Wednesday night, in part because the markets had factored in the inevitable hike, according to Investec’s Annabel Bishop.

There had been some expectation of a rout on the rand following the Fed decision. Instead, domestic events – namely the decision by the president to replace Nhlanhla Nene as finance minister with little-known Des van Rooyen – saw the rand’s value plummet to record lows of more than R16 to the dollar, she noted.

When the president was forced to make an about-face on his decision and appoint former finance minister Pravin Gordhan to the position a few days later, the rand recovered somewhat.

On Thursday morning the rand was trading in the region of R14.95 to the dollar.

After the events of last week, Moody’s revised its outlook on South Africa’s credit rating to negative, becoming the latest ratings agency to take a pessimistic view of the country’s economy.

In a statement Moody’s said that, along with the increased likelihood that economic growth would stay low, there was a rising risk of fiscal slippages thanks to both lower growth and “increasing political pressures”.

Moody’s said that, even without factoring in expensive new programmes the government has committed to, such as the nuclear build programme and National Health Insurance, political pressure was “calling into question the government’s continued ability to maintain spending constraint”.

But Gordhan’s appointment suggested that spending discipline would be maintained, the agency said.