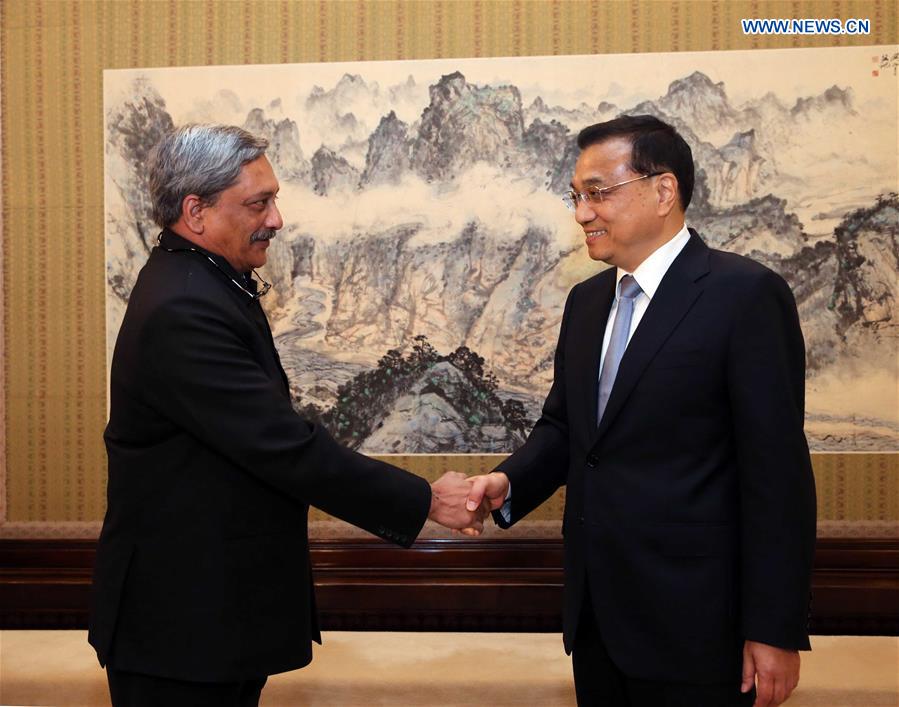

There is nothing unusual, but it is of much interest that Minister of External Affairs Sushma Swaraj met her Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, on the sidelines of the annual Russia-China-India trilateral talks in Moscow, even as defence minister, Manohar Parrikar, met his counterpart Chang Wanquan in Beijing. The emphases in these two meetings were not different, indeed as they should be, but they were also contrasting in tone and spirit. Swaraj had apparently raised the issue of Jaish-e-Mohammad leader Azhar Masood. China had blocked the Indian move to add Masood’s name to United Nation’s list of terrorists in the wake of the Pathankot terror attack in January this year. Chinese officials have clarified that their government did not exercise the veto in the matter, but it did not approve of it on the grounds that there was not sufficient information.

Meanwhile, the Chinese are willing to establish a hotline between the two militaries to control tensions on the ground along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The apprehension that the India-United States Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement was not to the liking of China is partially true but it did not in any way prevent the two sides from reaching a positive understanding in their bilateral relations. It is a reflection of the fact that the India-China relationship is a complex one, and that while there would be differences, and even sharp ones at that, in one sphere, there would be convergence of views and a lot more positivity in another area. The meetings of Swaraj-Wang and Parrikar-Chang underline this fact.

As there are many in India’s strategic community who frown on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), there would be hawks in the security think-tanks in the Chinese establishment who would be watching the India-US rapport on strategic and security issues. The concerns are legitimate on both sides, but in a complex world, the apparently conflicting engagements do not adversely affect bilateral relations. India and China like any other two countries are bound to pursue different goals, and even in the case of conflict of interest — as in the case of Chinese support for Pakistan or India’s rapport with the US in matters relating to South China Sea – the two countries do not turn away from each other, much less break off ties. Mature countries recognise that mutual interests do not rule out divergences.

It is, however, necessary to point out that it is not necessary for India to be unduly apprehensive about China’s, or even the US’s support for Pakistan. It is indeed the case that Islamabad is leveraging its ties with Beijing and Washington when it deals with New Delhi. There is no doubt that the Chinese and Americans are not averse to hedge India in indirectly through Pakistan. The thumb rule that your enemy’s enemy is your friend, or the converse that the friend of your enemy is your enemy does not really hold good in the real world of international relations. Indian security experts will have to learn to perceive the world with its many layers instead of viewing it in a binary fashion. As with Pakistan, there is a tendency among the experts in India to view India-Japan relations in terms of China-Japan relations. It has to be understood that even the US and Russia, Saudi Arabia and Iran, China and Japan are aware of the dreadful fact that they would need to act together at times. India will then have to weigh its options with regard to neighbours, friends, rivals and detractors in terms of a matrix that is sufficiently complex to reflect the real world.