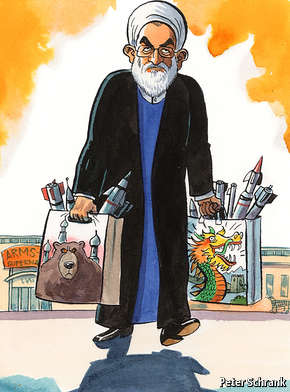

Should Russia and China expect an arms bonanza from Iran?

AMONG the many concerns voiced at Barack Obama’s summit with Gulf Arab leaders this week was that a nuclear deal with Iran will open the way to sales of sophisticated weaponry to the Islamic Republic. Already there is tension between America and Russia over the continuation of the restrictive arms embargo imposed by the UN Security Council in 2010.

Less than a fortnight after the framework deal was reached on April 2nd, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, lifted a ban on supplying the S-300 air-defence missile system to Iran under the terms of a $800m contract signed in 2007. The Russians maintain that the ban on the sale had been purely voluntary because UN Security Council Resolution 1929 only forbids the transfer of offensive weapons. But Russia is making little secret of its desire to sell a lot more military kit to the Iranians. In January, Sergei Shoigu became the first Russian defence minister to visit Tehran for 15 years, while Russia’s main negotiator at the Iran talks called for the lifting of the arms embargo “immediately after [final] agreements are reached”. Russian commentators estimate weapons sales to Iran could reach $13 billion. Whether Iran has that kind of money is another matter.

The American view is that while all UN nuclear-related sanctions will be lifted simultaneously once Iran has fully complied with a final agreement, “important restrictions on conventional arms and ballistic missiles” will be re-established by a new UN resolution. A meeting in Sochi this week between Mr Putin and John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, mainly to discuss Ukraine and Syria, also sought a compromise on future arms sales to Iran. Mark Fitzpatrick of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London expects there to be a new resolution but one which allows Russia “some carve-outs for its defence industry”.

Whatever is formally agreed, it seems likely that the international legitimacy that Iran expects to gain from a nuclear deal will give it growing access to military technology from both Russia and China, Iran’s biggest trading partner, if not from the West (neither America, Britain nor France will jeopardise their lucrative weapons contracts

with Gulf Arab states). But for all the talk of Iran’s ambition to be a regional hegemon, its conventional military capabilities are relatively feeble. Decades of sanctions, distrust of foreigners, attrition suffered during the Iraq war and an indigenous industry hampered by corruption and lack of access to technology have all taken their toll.

Iran’s air force is antiquated, consisting mainly of American aircraft bought by the Shah. Dependent on spares scavenged on the black market, only about half are serviceable. Although large, its poorly equipped land forces, split between the regular army and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), are structured to prevent coups and conduct irregular warfare against an aggressor, rather than to threaten neighbours. The IRGC aids and trains proxy forces outside the country that serve Iran’s strategic aims, such as Hizbullah in Lebanon (which confronts Israel and is fighting in Syria), the Shia militias in Iraq and the Houthis in Yemen. With more money from oil revenues and a stronger economy, Iran’s appetite for meddling may well grow. But it lacks the capacity for traditional military power projection that made Saddam Hussein such a menace.

To compensate for this weakness Iran, with Chinese and North Korean help, has acquired considerable missile know-how which it has used to develop so-called anti-access/area denial capabilities in waters near its own coastline. Shore-based anti-ship missiles, fast missile boats, midget subs and conventionally-armed ballistic missiles that threaten its enemies’ air bases, refineries and oil terminals are intended to be a deterrent against the more powerful forces Iran sees ranged against it.

And those forces certainly are powerful. Saudi Arabia’s defence budget is five times bigger than Iran’s. Together, the Gulf Co-operation Council countries outspend Iran on defence by more than seven to one and have access to some of the most sophisticated weapons the West can offer. America’s Fifth Fleet is based in Bahrain, and it has air bases throughout the region. Iran will take decades not years to rebuild its atrophied conventional military capabilities. It knows how to make a great deal of trouble when it wants to, but a potentially dominant military power it is not.