Jan 16th 2014, 10:54

THE year did not begin well for Dilma Rousseff. The real ended 2013 one-third weaker against the dollar than when she took office as Brazil’s president three years ago. Car sales were down for the first time in a decade. More dollars flowed out of the country than at any time since 2002.

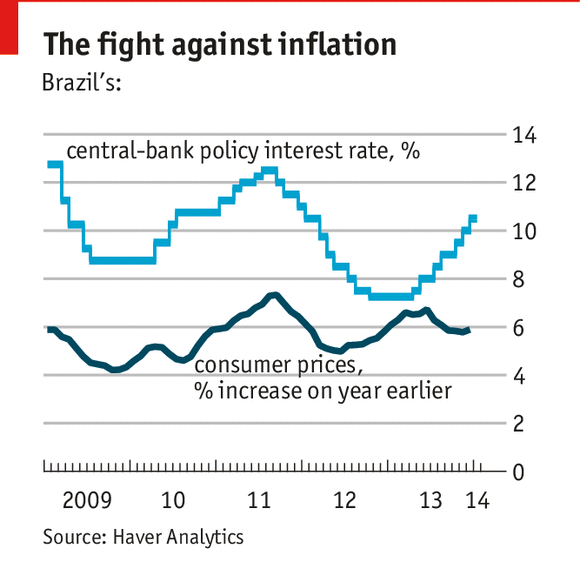

Most perniciously, on January 12th the bean-counters announced that inflation hit 0.92% in December, the highest monthly rise in ten years. That pushed the annual figure to 5.91%, above market expectations. The jump prompted the Central Bank to raise the main interest rate on January 15th, not—as analysts had long forecast—by a quarter of a percentage point, but by half a point, to 10.5%.

Inflation is a Brazilian bugbear. The economic costs are clear: high inflation hits both the poor, struggling to make ends meet, and the indebted middle classes as interest rates rise. But it is also a political issue. Most adults recall the hyperinflationary era of the early 1990s, when shopkeepers would adjust prices each morning, and then change them again in the afternoon.

The Central Bank governor, Alexandre Tombini, was quick to blame a strong dollar and high commodity prices. A November readjustment of prices by Petrobras, the state-owned oil giant, did play a role. But food in shops was dearer, too, even as wholesale prices edged down. Economists also finger easy credit, a tight but unproductive labour market and wasteful public spending.

Ms Rousseff has been doing what she can to keep prices down. In 2012 the government had slashed the fuel duty to zero, where it has remained. Last year it held down public-transit fares (a proposed rise, later reversed, sparked huge nationwide protests in June), lowered taxes on staples and postponed until further notice a tax hike on drinks passed in October. The state-owned electricity generator slashed bills by 16%, the biggest cut in 20 years; Estado de São Paulo, a newspaper, puts the subsidy at 29 billion reais ($12 billion) in 2013.

Absent such tinkering, says Tony Volpon of Nomura, an investment bank, inflation would almost certainly have exceeded the Central Bank’s 6.5% upper bound. Regulated prices were up by 1.5%; free ones climbed by 7.3%. This discrepancy is unsustainable. If the government does not let state-controlled firms adjust their pricing, warns Mr Volpon, they will go belly up. Nor can it keep propping them up without doing irreparable damage to already-fragile public finances.

In the event the fiddles failed to help the government fulfil its pledge to stop inflation topping the 5.84% recorded in 2012. And they leave Ms Rousseff little room to absorb potential price shocks this year. Hernon do Carmo of the University of São Paulo thinks inflation is likely to breach the Central Bank’s target range. Mr Volpon reckons the interest rate will hit 10.75% come the autumn. With prices high and interest rates close to where they were when Ms Rousseff took office in 2011—after dropping to an historic low of 7.25% for six months in 2012-13—voters will be feeling pinched as they cast their ballots.

Even though Ms Rousseff remains the clear favourite in the presidential poll this autumn, the price rises may damage the chances of her Workers’ Party (PT) in congressional and state elections. Opposition politicians are rubbing their hands. Alvario Dias, deputy speaker of the senate from the centrist Party of Brazilian Social Democracy, told Estado that inflation will cast a shadow over the election. “It’s what elects or defeats governments.”