Although China has conventionally seen the Middle East as mostly an energy source, the country has developed a new framework, which would expand cooperation.

China’s Foreign Ministry released a policy paper on the Middle East in January, and continues to look for new ways of cooperation.

“In the policy paper, the framework of the relations are explained using the ‘1+2+3 cooperation pattern,’ with energy cooperation as the ‘core,’ infrastructure construction and trade and investment facilitation as the ‘2’ wings, and nuclear energy, space satellites and new energy as the ‘3’ breakthroughs,” China-Turkey ties analyst Umut Ergunsü wrote in Turkey’s Hurriyet Daily.

China currently exports consumer goods to Middle Eastern countries, and is developing nuclear energy cooperation with Jordan. However, its attempts to inject itself into the Middle Eastern policy debate have not brought many results.

Sunni Shift?

Because China has thus far avoided making a principled position in the Middle East, increased confrontation in the region has meant taking increasingly shaky diplomatic steps.

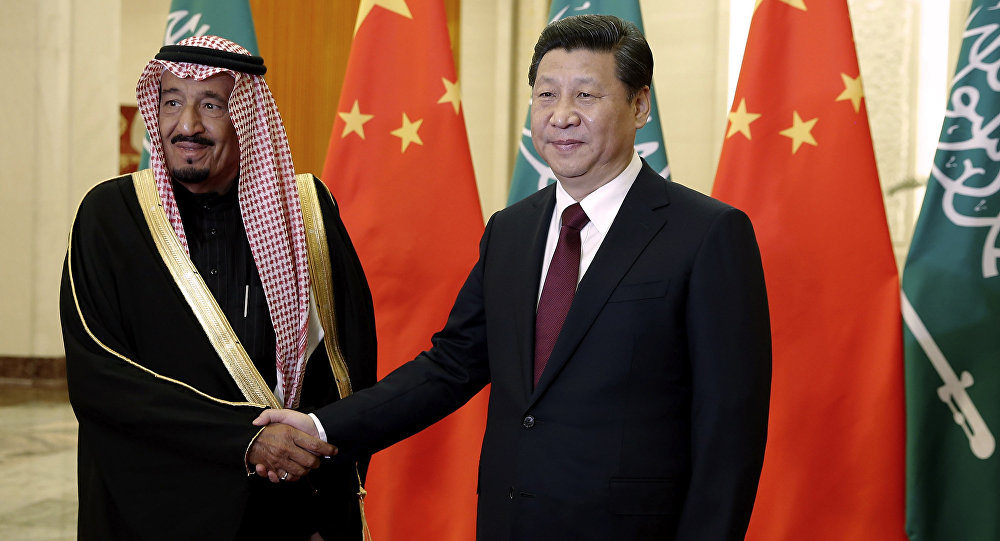

China recently attempted to host its own Syrian peace talks, abandoning its unequivocal support of Bashar Assad. It supported Saudi Arabia’s position on Yemen in the UN Security Council, while at the same time cancelling a visit to Riyadh to avoid tensions with Iran.

According to Gal Luft, co-director of the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, the moves could be a reaction to the reduced role of the United States in the region and Russia’s moves in Syria.

“China has for several months harbored a suspicion that the United States, entering an election year while drowning in domestic oil and gas supply, is not as interested in the Middle East as it has been for the past half century,” Luft wrote in Foreign Policy.

While such a shift does make sense, not being familiar with all the players could spell trouble for China, as it runs the risk of alienating its current partners and not significantly improving ties with other players, such as Saudi Arabia.

Party of Business

While China has made inroads in the Middle East because of its business interests, carrying out a proactive foreign policy was mandated at the Party level.

While the “One Belt One Road” policy is seen as the driver for the new change, disappointments in previous party policy set by Deng Xiaoping. The policy backfired in 2011 in Libya, where China lost a considerable share of investment projects because of NATO intervention in the country’s conflict and subsequently, another civil war.

The Libyan civil war also led to China’s first foreign military action since the Deng Xiaoping era, when China evacuated its workers from the country.

“The events in Libya showed that no economic might can compensate the lack of necessary military-political instruments to assert influence,” Vasily Kashin, senior fellow at the Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies wrote in 2012.

Whether China’s new course is able to prove that it is capable of being an effective mediator in the Middle East, could depend on how deeply it is willing to get involved.